Future Ethics

About my favourite design read of 2019

Future Ethics by Cennydd Bowles is easily my favourite read of last year and one of those books that I wish I had during my design school days. Whether you're working in the tech industry as a developer, designer, manager or perhaps a CEO: the moral choices we make in our work shape our products. This can have profound (often unforeseen)consequences on our users and—on rare occasions—lead to real-world harm or mistreatment. A part of the solution herein lies that a better understanding of the frameworks to clearly articulate our intentions and choices to each other would greatly benefit us all.

Future Ethics helped to demystify ethics beyond the trolley problem we’ve already heard of so many times before. The book is chock-full of interesting examples of ethical dilemma’s in privacy, systemic bias, fake news, the internet of things, AI and autonomous warfare. I appreciate that—while taking plenty of firm stances on his own—Bowles often acknowledges that many major issues could have different solutions depending on the way you look at them. In the book, he articulates three different lenses (deontology, utilitarianism and virtue ethics) to approach most dilemma’s.

These words are likely as unfamiliar to you as they were to me, so here’s a quick rundown:

- Deontology ethics are based on a set of moral rules to guide decisions. Through the eyes of a deontologist, actions can be inherently right or wrong regardless of their consequences. Suppose you find a lost iPhone in the grocery store. If you’re a deontologist, you might consider that ‘stealing is wrong’, and will be inclined to turn the phone over to the store manager regardless of whether you would be able to get away with keeping it for yourself: it’s simply the right thing to do. Now this example was pretty black and white, whereas the real world often presents more nuanced dilemma’s, so to navigate these situations, a common deontological test is by asking the question ‘do I treat other people as a means to an end?’. If the answer is yes, this person is less inclined to take that direction.

- Utilitarianism ethics focus on the expected outcome, choosing the side that makes the most people happy or delivers the most positive upside to the biggest number of people. A common practice of utilitarianism in the tech industry is the cult of minimum viable products—where teams deliberately ship the smallest functional part of a product or feature—to bring value early on to most of their users while acknowledging there are still many improvements to be added later on.

- Virtue ethics revolve around moral character through virtues, a concept coined by Greek philosopher Aristotle. Where deontologists base their decisions on duty and utilitarians on outcomes, virtue ethics encourages individuals to reflect on the kind of person they aspire to be, and how to exemplify that behaviour. If you value ecological sustainability, you might consider cutting down on flight travel or meat consumption as virtuous behaviour. Bowles describes the newspaper test—“would I be happy for my decision to appear on the front page of tomorrow’s news?”—to be a good entry point for considering your decisions based on virtues.

Deontology, utilitarianism and virtue ethics will provide different arguments, and often different resolutions to a dilemma, yet it’s important to remember one is not necessarily “better” than the other. Neither are these lenses to be treated as mutually exclusive, some dilemmas can benefit from a combination of ideas from different ethical lenses at once. Although it’s certainly a step in the right direction, being able to differentiate between these concepts won’t make you a better designer, developer or manager right away. Developing your intuition takes time and real-world experience.

That said, how you apply ethics within your line of work, when to speak up or when to let things go, is up to you, and based on the situation at hand. You will make mistakes, but learning to discuss the moral intentions of the software we build is vital if we want to thrive as an industry. Especially since big tech has been under so much scrutiny over the years for their inability to act on pressing matters around privacy, battling hate-speech, inclusion and mental wellbeing.

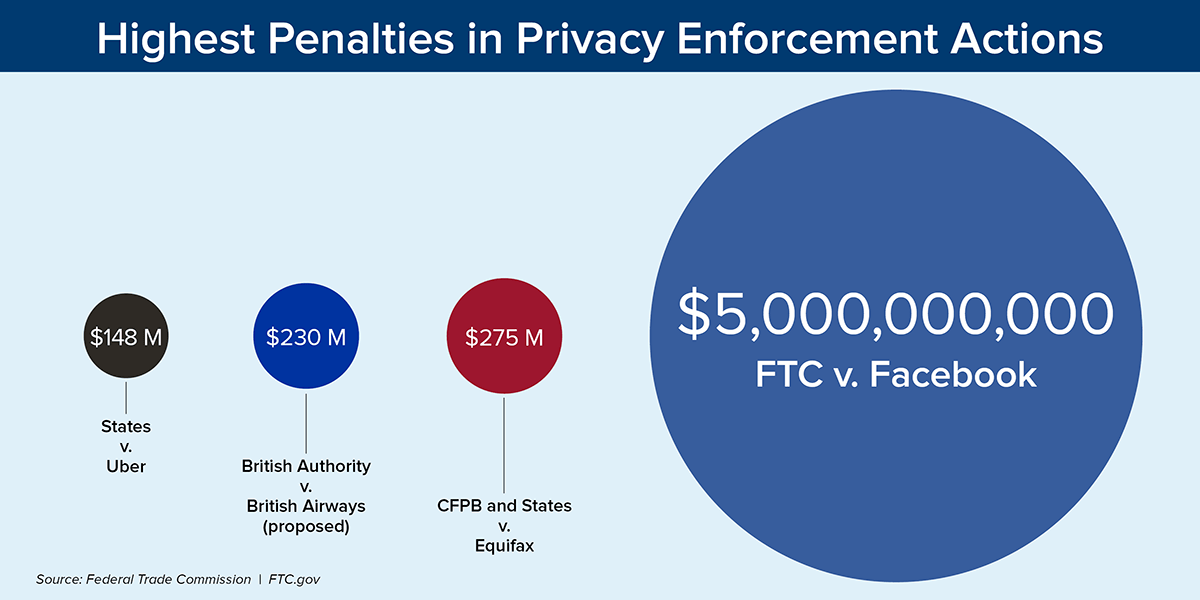

While the regulatory body is still years behind our industry, it can definitely slap companies on the cheeks if they fail to take responsibility for their actions. In late July last year, Facebook was hit with a record-breaking five billion dollar fine by the Federal Trade Commission for privacy violations. Delegating the moral responsibilities of a company to an external body is a mistake, as Facebook will attempt to dodge responsibility again when their own business model will inevitably usher them into the next controversy.

History has shown us that—given enough time and negative public opinion—governments will always find a way to regulate emerging industries if they fail to regulate themselves (exemplified by the GDPR & CCPA), to protect, yet often strain the end-user and new innovations. Any real moral change should therefore come from within, by the people that help to build the software, conduct a/b-experiments, and oversee the roadmaps. This book helps us get there.

Whether you want to improve how you communicate when explaining difficult choices, or if you’re generally interested in ethics, I wholeheartedly recommend you to give Future Ethics a try. Find it on Bowles’s website here.